A History of Antivivisection from the 1800s to the Present: Part I (mid-1800s to 1914)

Note from the author: This overview of the history of antivivisection was published in three parts in Veterinary Heritage, the bulletin of the American Veterinary Medical History Society, in May 2008, November 2008 and May 2009.

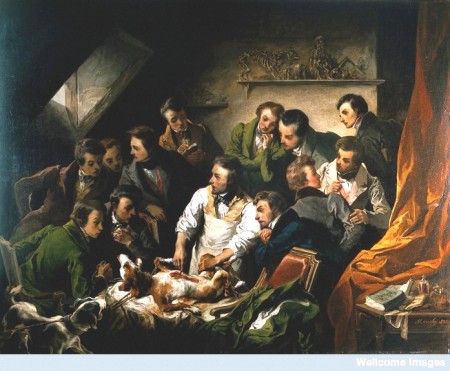

A physiological demonstration with vivisection of a dog. Emile-Edouard Mouchy, oil painting, 1832.

Foreword and Introduction

The human-animal bond as a marketed concept, even as a “veterinary meme”, has been with us for over a decade, and in its positive aspects, it is meant to highlight the happy aspects of owning and caring for a pet, zootherapy and an overall desire to connect in some way emotionally or existentially with non-human sentient beings. However, in the author’s opinion, the human-animal bond has a darker side that casts a long shadow over our relationships with companion animals as well as all other species that have been used in research. This historical overview stems from an examination of past and present issues in the place of non-livestock animals in society, and how they have been and continue to be used in ways that are potentially troublesome for contemporary veterinarians in the Western world.

The overview is divided into three periods, the first of which is appearing in this issue of Veterinary Heritage. Part I begins with the rapid expansion in the field of physiological experiments triggered by Bell and Magendie’s research in the mid-1800s and culminates with the First World War. During this period, a surging popular and philosophical reaction to animal experimentation is described, a response that arguably hit its peak during the Edwardian period in England, and was subsequently muted due to the catastrophes and sociopolitical transformations that occurred during and immediately following the First World War.

Part II covers the years from 1918 to approximately 1970, and Part III summarizes various developments in animal rights philosophy from the 1970s to the present.

The philosophical and social transformations that characterize each of these periods both influenced and were influenced by progress in medical and scientific knowledge that often resulted directly from the use of animals in research and experimentation. But more specifically to antivivisectionist philosophy, the writings of influential authors and philosophers that surfaced during each period were crucial in reformulating a consideration for animals – particularly with regard to the tensions and dilemmas of deliberately causing suffering and distress in animals that are widely recognized as feeling and thinkinga beings – even in light of these gains.

PART I Vivisection from the Mid-19th Century to the First World War: A Growing Body of Physiological Knowledge

It would be hard to overestimate the impact of the experiments and demonstrations carried out on living animals in the 19th century on subsequent developments in physiological knowledge and applications for human medicine. What is perhaps less obvious from a historical viewpoint is the experiments’ impact on the experimenters themselves – not to mention on public perception of the time. Yet it is sufficient to examine only a few of the most significant experiments to understand the impact and the “ethical dilemma” they continue to pose today.1,2

The French physiologist François Magendie (1783-1855) and the Scottish anatomist Charles Bell (1744-1842) can both be credited with one of the most significant single discoveries in physiology, which had an immediate influence on medical research and practice.1 The discovery that the dorsal and ventral spinal nerve roots have different functions – the dorsal roots carrying sensory information and the ventral roots conveying motor signals – later became the basis for the study of the spinal reflex arc by Charles Sherrington (1857-1972). The establishment of the field of neuroscience hinged on this basic understanding of the reflex arc.

Of the two, Magendie’s work was more precise and explicit, though it was predated by Bell’s experiments by 11 years. As Sechzer has pointed out, Bell’s failure to describe the precise function of the dorsal roots can be attributed to his reluctance to perform more than one experiment on a living rabbit whose dorsal spinal roots were sectioned by the experimenter himself. At the time, Bell said: …I was deterred from repeating the experiment by the protracted cruelty of the dissection. I therefore struck a rabbit behind the ear, so as to deprive it of sensitivity by the concussion, and then exposed the spinal marrow.1 If the rabbit had been conscious, Bell would likely have demonstrated, as Magendie later did, that the dorsal roots conveyed sensory information.

In contrast to Bell’s more hesitant approach, Magendie used several six-week-old puppies in his published series of experiments. In these young animals, the vertebral column is not yet ossified so it can be easily separated to expose the spinal cord. He was then able to cut the dorsal and ventral roots of the nerves at the point where they emerge from the spinal cord, first singly, then together, and observe the results in terms of loss of sensation, movement, and both. In succeeding studies, Magendie repeated and varied the experiments, using different animal species. It should be noted that both Bell and Magendie’s experiments were carried out prior to the application of ether, the first chemical agent used to procure anesthesia.1,3

Meanwhile, Bell was making his distaste for animal experimentation very clear, possibly reflecting a social climate that was itself hostile to the liberties taken by anatomists and physiologists with the living bodies of animals. In his correspondence, he stated:

I should be writing a third paper on the nerves, but I cannot proceed without making some experiments, which are so unpleasant to make that I defer them. You may think me silly, but I cannot perfectly convince myself that I am authorized in nature, or religion, to do these cruelties – for what? – for anything else than a little egotism or self-aggrandisement; and yet, what are my experiments in comparison with those which are daily done? And are done daily for nothing.4

Whether or not Bell’s statements were a pointed attack on Magendie’s repeated experiments, they do demonstrate an understandable ambivalence towards the deliberate act of causing suffering in the pursuit of knowledge – and they also highlight the fact that useful results did not systematically emerge from painful and extremely invasive interventions. Physiologists of the era could not have known if their chosen approach or theory would result in illumination or simply a multiplication of butchered and decomposing animal corpses in laboratories which, compared to modern standards, were ill-equipped to adequately dispose of them.

Magendie’s immediate successor at the Collège de France was Claude Bernard (1813-1878), who had served from 1840 to 1850 as “preparer” or assistant to Magendie’s experiments.5 An aspiring playwright, Bernard was instead persuaded by critics to find his métier in a different field. A fortuitous career change, it turned out, as Louis Pasteur would eventually laud him as “not merely the Father of Physiology, but Physiology itself.” Among his many significant and undisputed contributions to physiology, nutrition, pathology and pharmacology, his animal experiments using the curare poison illustrate the most difficult aspects of vivisection.

Bernard did not have a well-developed theory in mind when he began his work in 1849 with the alkaloid toxin from South America. He was curious about its action, by the “peacefulness” of death, and the lack of visible suffering in the victim. We now know that curare works only at the specific site where a nerve meets the muscle, causing paralysis by preventing the nerve impulse from making the muscle contract. Death comes when the nerve-controlled respiratory muscles no longer function and the victim is asphyxiated. The “peacefulness” of death is an illusion: the poisoned individual lacks the ability to express pain and distress. Bernard’s awareness of this reality is apparent in his writings, even though the precise action of curare at the neurosynaptic level was out of his reach. He continued to devise new ways of using the poison experimentally on animals until the end of his life.1 Tellingly, Bernard’s wife became a vocal opponent of vivisection and she separated from him in 1870, but her dowry had already been spent in financing his research.6

As one of the direct results of the curare experiments, it was eventually recognized that other drugs had certain specific sites of action. This concept of drug receptors or specific targets would become a key one for pharmacological research at the turn of the century and beyond.6,7

Even though Magendie and Bernard were aware of the nature of opposition to their work, they firmly believed that vivisection was justified by the potential possible benefits to humanity, particularly with regard to furthering knowledge of physiology and medicine as well as avoiding the use of human subjects. In his book, An Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine, Bernard explains his conviction on the value of vivisection:

Have we the right to make experiments on animals and vivisect?…I think we have this right, wholly and absolutely. It would be strange indeed if we recognized man’s right to make use of animals in every walk of life, for domestic service, for food, and then forbade him to make use of them for his own instruction in one of the sciences most useful to humanity. No hesitation is possible; the science of life can be established only through experiment, and we can save living beings from death only after sacrificing others. Experiments must be made either on man or on animals. Now I think that physicians already make too many dangerous experiments on man, before carefully studying them on animals. I do not admit that it is moral to try more or less dangerous or active remedies on patients in hospitals, without first experimenting with them on dogs; for I shall prove, further on, that results obtained on animals may all be conclusive for man when we know how to experiment properly.8

Proper experimentation, perhaps what would be referred to today as methodology, protocol, or guidelines, was therefore a key concern – though an admittedly ill-defined one – of experimental physiologists in the 19th century, conscious as they were of the mounting public awareness of and opposition to animal experimentation. Various individual reactions to the very acts of cutting into living flesh, causing irreparable damage to individual animals and observing animal reaction to pain and distress that was a perfect mirror of human reaction, surely caused some or many experimenters to be ill at ease with their own work – in spite of any benefits in terms of knowledge gained. Charles Darwin (1809-1882) was himself a very reluctant vivisectionist; he was often “appalled” at his own experiments on pigeons.9

Some experiments took place as simple demonstrations for the benefit of students and practitioners, as a form of verification or proof; and in addition to novel experimentation, there was also a gradual trend toward reproducing the effects of classical experiments in college laboratories throughout Europe and North America.10 In a graphic description from the Montreal School of Medicine and Surgery in 1847, we have one of the earliest accounts of the use of animals in research in Canada. This experiment on a dog, carried out in the presence of a dentist, two physicians, several medical students and an artist, was performed by Horace Nelson, a lecturer on anatomy at the school, with the goal of demonstrating the anesthetic efficacy of ether. It should be noted that the first published account of the use of ether in human dentistry had already been published in 1846, and ether had recently been used with success in human surgery.3

Nelson’s written account describes the dog as being in a state of “profound insensibility” after four minutes of ether inhalation, and the experiments as consisting of a series of incisions and amputations: removal of an ear, an incision from the hind leg extending to the neck, partially flayed open, followed by amputation of a foreleg. At that point, Nelson’s vivisection was interrupted by a clinical visit to a patient. When he returned, he proceeded to remove the other ear, but noted that the dog’s “violent efforts and cries giving everyone present to understand, that he was no more sleeping.” The dog was then “instantly strangled”, putting an “end to his sufferings.” Nelson went on to obtain a second dog within a few days and he performed another series of experiments to “prove conclusively, if full confidence could be placed on the effects of the inhalation.” The graphic account of the experiments contains sensually descriptive and emotional language, and Nelson himself called the sessions “cruel and lengthy”:

Several deep incisions were made in the muscles of the back…and I once more applied the poker to staunch the bleeding of several small arteries; not a moan was heard, not the least starting of a nerve was perceptible…by means of a crucial incision, I laid open the abdominal cavity and took out upon the table the mass of intestines; my students had then the advantage of a demonstration of the peristaltic motion of those organs…the liver and spleen torn and wounded…10

At the end of the experiment, the dog was allowed to wake, whereupon he tried to “lick his numerous wounds and…to rise, but was so much exhausted by the profuse loss of blood that he fell back on the table.” At that point, this animal was also strangled.

As Connor notes in his paper, the emotional tone of this type of experimental account was striking in its indication that the experimenter was deeply aware of the animal’s suffering, and was relieved when it was finally over. Connor also observes that the emotional and highly descriptive tone of the account began to “disappear from scientific discourse in Canada and elsewhere.”10

Antivivisectionism from the Mid-19th Century to the First World War

While the scientific world was coming to terms with the nature of the progress taking place through animal experiments, by adopting and refining clinical language and the passive voice, the opponents of vivisection were not similarly constrained to modifying or suppressing their language, moral views and even identification with the animal victims of experimentation. The antivivisectionism that developed rapidly from the mid-19th century can be subdivided into a variety of origins and motivations, including: moral/religious; feminist/suffragist (political and gender-related); and humanist opposition, via an exploration of human identity, romanticism, and identification with animal consciousness. Some of these currents of opposition were united on issues other than antivivisectionism, while on other social and moral issues they did not necessarily find common ground. In England, antivivisectionism found an important ally in Queen Victoria herself.6

Religious and moral opposition

Religious points of view on vivisection have been well-documented and commented on in many excellent papers.1,2,9,12

Christianity in England during the Victorian era was primarily Protestant and Anglican with strong evangelical and Quaker influences in certain social spheres. Evangelicalism and Quakerism, with their emphasis on personal piety, charity and “good works” – which often resembled activism with a missionary-like devotion – were particularly drawn to the antivivisectionist cause. This was not in the least because of a concomitant distrust in scientific progress: due to a human-centered focus and aspirations for a better world that would be achieved through human effort and increased knowledge, this distrust was intensified by Charles Darwin’s evolutionary theory, published in On the Origin of Species in 1859. For many people in these religious movements, the principal or even sole literary and cultural reference was the Bible, and the notion of forbidden fruit, the “tree of knowledge of good and evil” and fallen human nature was therefore central in their views on the morality of all human activity. However, there was likely an equally strong Biblically sourced notion that animals existed “explicitly for man’s benefit and rule; no item in the physical creation had any purpose but to serve man’s purpose”.9 Different interpretations of the Genesis creation account and the morality of animal use in experimentation doubtless caused much debate and tension in theological and clerical circles of the time.

During the 1840s, Claude Bernard recorded an account of a Quaker who visited François Magendie. It is likely that the Quaker represented the prevailing view of both Quakers and evangelicals when he said:

Thou performest experiments on living animals. I come to thee to demand of thee by what right thou actest thus and to tell thee that thou must desist from these experiments, because thou hast not the right to cause animals to die or make them suffer, and because thou settest in this way a bad example and also accustomest thyself to cruelty.13

Possibly one of the most unlikely and yet ultimately influential denouncers of animal cruelty and by obvious extension, vivisection, was Anna Sewell (1820-1877). Sewell wrote the children’s literature classic Black Beauty, the first widely published English language novel written from the perspective of an animal (a “first-horse” narrative).14,15,16 Sewell, born to a religious Quaker family in Yarmouth, was no stranger to writings on religious morality, and was very active in missionary works such as teaching Sunday School, educating workers on morals and religion at an evening institute and joining her mother’s temperance activities. Black Beauty was her sole novel, published when she was 56 years old, just a few months before her death. Sewell’s explicit purpose was to highlight the various hardships to which horses were subjected in the Victorian era, through deliberate cruelty, neglect, ignorance and even devices such as the check-rein, a bearing rein or strap that was used to keep a horse’s head fashionably high, but which was painful and damaging to the neck with repercussions on the posture and gait.16 The book was widely promoted and used by groups seeking more humane treatment of horses and the elimination of the check-rein; thousands of copies were distributed to horse handlers and drivers in the effort to restrain the abuse of working animals. Anti-cruelty groups gave the novel very positive reviews, and the book ended up being very popular among schoolchildren. By 1923, the publisher claimed that the novel was the sixth best-selling book in the world, and it was made into movies and TV programs at various times during the 20th century.

The connection between Black Beauty and antivivisectionism has multiple angles18: it was effectively the first novel written from a non-human point of view and introduced a new popular literary means of exploring animal existence through empathetic imagining, and non-invasive observation of physical conditions. Second, the book was distributed to schoolchildren, and as a result, a rising generation was explicitly encouraged to identify with an animal’s point of view, with a heightened possibility for emotion and empathy. Third, Black Beauty was a direct inspiration for other writers to explore the animal world in their imaginative, anthropomorphic and empathetic writings. Well-known novels and stories such as Beautiful Joe (1893), a Canadian novel about an abused dog based on a true story17, The Wind in the Willows (1908) and the Beatrix Potter books were all directly or indirectly inspired by Sewell’s novel, introducing a whole new focus in children’s literature and empathy for animals in the English-speaking world that continued to develop and expand throughout the 20th and into the 21st centuries.

Humanist opposition

Nineteenth-century opposition to vivisection was not limited to sentimental children’s writers and religionists. Arguably, many if not most of the great novelists and writers of the mid to late-19th century were vehemently opposed to vivisection, basing their reaction on existential, moral, aesthetic and classical humanist grounds. Some even voiced fears regarding the human capacity for rapacious “progress” that could (and as it turns out, did) occur in the future.

The burgeoning literature of the 19th century, and in its most refined form, the novel, provided educated men and women with the means to express thoughts, imaginings, consciousness as well as factual observation in a form that was easily accessible to others, allowing for exchanges and development of ideas and principles. The humanist writers of the late 19th century possibly represent the apogée of a cohesive view of non-religious human morality. As such, their writings had power and influence, if not in politics and science, at least on individual readers and in certain spheres of society.

But the sphere that appeared to be distancing itself the most from the reach of moral and artistic literature was science – experimental science in particular. The increasing need for many years of training to acquire the basics of scientific knowledge and method began to place a significant barrier between the humanities and the applied sciences. It was becoming more difficult for individuals, no matter their level of education, to straddle the barrier between scientific, experimentally acquired knowledge, and literature and philosophy. It is important to note that even though both types of knowledge are based on fact and observation, the conclusions and methods employed – not to mention the desired ends – are often at odds. The following citations from a selection of well-known late-19th century writers illustrate the way in which vivisection represented a fundamental divide between science and letters:

Charles Dickens, novelist (1812-1870): “The necessity for these experiments I dispute. Man has no right to gratify an idle and purposeless curiosity through the practice of cruelty.”

Robert Browning, poet (1812-1889): “I despise and abhor the pleas on behalf of that infamous practice, vivisection… I would rather submit to the worst of deaths, so far as pain goes, than have a single dog or cat tortured to death on the pretense of sparing me a twinge or two.”

Leo Tolstoy, Russian novelist and social reformer (1828-1910): “What I think about vivisection is that if people admit that they have the right to take or endanger the life of living beings for the benefit of many, there will be no limit to their cruelty.”

Lewis Carroll, mathematician and author of Alice in Wonderland (1832-1898): “Forbid the day when vivisection shall be practiced in every college and school, and when the man of science, looking forth over a world which will then own no other sway than his, shall exult in the thought that he had made of this fair earth, if not a heaven for man, at least a hell for animals.”

Mark Twain with kitten

Mark Twain, American lecturer, writer and humorist (1835-1910): “I believe I am not interested to know whether vivisection produces results that are profitable to the human race or doesn’t. To know that the results are profitable to the race would not remove my hostility to it. The pain which it inflicts upon unconsenting animals is the basis of my enmity toward it, and it is to me sufficient justification of the enmity without looking further.”

George Bernard Shaw, playwright (1856-1950): “Vivisection is a social evil because if it advances human knowledge, it does so at the expense of human character.”

Political and gender-related opposition

There is ample evidence of a clear link between the nature of animal experiments and the form of oppression to which women in the Victorian era were subject.18,19 Female oppression in that era included the ideas of victimhood; animals and women as property and without the rights that derived from owning property; submission to male/human authority; parallels between the restraining and surgical devices used on animals and in the medical treatment of women, including childbirth customs and gynecological examinations; as well as the imagery in some types of Victorian pornography.18

Frances Power Cobbe (1822-1904) was one of the earliest and possibly most effective feminist theorists and pioneer animal rights activists. In 1875, she founded the world’s first organization to campaign against animal experiments, the National Anti-Vivisection Society, alternately known as the Society for the Animals Liable to Vivisection, and in 1898, the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection, two groups that are still active today.20 When Charles Darwin, in his dotage, wrote a letter to the London Times in 1876 to complain about the growing influence of the antivivisectionists, it was undoubtedly with Power Cobbe foremost in his mind: “from the tenderness of their hearts…and their profound ignorance, [they] opposed all animal experimentation.”11 However, antivivisectionists were neither predominantly female nor ignorant; in fact, the founders of the National Anti-Vivisection Society included clerics, poets, writers, social reformers, and even a former vivisectionist (George Hoggan) and each of the original members based their opposition to animal experimentation on what they believed to be explicitly Christian principles. There is nonetheless a basis to conclude that many political and well-educated women were key opponents of vivisection, and that their active opposition grew significantly during the Victorian and early Edwardian periods.21

A significant aspect of feminist antivivisectionism was due to the significant gender barrier and strong cultural resistance to the acceptance of women into medical faculties and general practice.21 This placed the few women doctors who succeeded in becoming qualified physicians on the margins of the profession, far from the demonstration and experimentation laboratories where vivisection, dissection and animal use was taking place. For one thing, most women’s medical colleges were actively antivivisectionist.

Yet there was at least one prominent late-19th century woman physician, Mary Putnam Jacobi (1842-1906), who early on in her career adopted a very different stance with regard to vivisection.22 Jacobi was a European-trained physician in New York who vigorously practiced vivisection throughout her career, and made a calculated decision to deliver a pro-vivisection lecture to the Massachusetts Medical Society in 1889. Her stance illustrated the fact that a scientific identity and approach were perceived foremost to be masculine aptitudes; her advocacy of scientific medicine was therefore a medical and political strategy to advance her own professional status as well as the political status of women. This was in direct opposition to the common perception of Victorian, “sentimental” antivivisectionist feminism. Jacobi’s goal was to carve out a place for women in the laboratory, the site of hands-on investigative opportunity, where logic, methodology and ultimately scientific and medical authority – which translated into a form of power – could be acquired. Putnam Jacobi represents an alternative point of view in the feminist connection to vivisection, but her pro-vivisectionist pro-feminism neither prevailed nor disappeared from the debate as it spilled over into the 20th century.

The Brown Dog Affair: uniting women suffragists, workers and popular sentiment against vivisection

A series of minor riots took place in London in 1907 when medical students from the University of London attacked the bronze statue of a brown terrier dog (known as the “Brown dog riots” or “Brown dog affair”).23 The statue was commissioned in 1906 by antivivisectionists to commemorate a terrier vivisected in laboratories during 1903, along with the 252 other dogs that had been killed there the previous year. The vivisection of the brown dog had been carried out by brothers-in-law Ernest Starling (1866-1927) and William Bayliss (1860-1924) in their work on pancreatic secretions, work that would lead over the next few years to the naming of the first hormone, secretin. Their experiments included the physical demonstration that hormonal action was independent of nervous system stimulation. The brown dog, likely a stray found wandering the streets of London, was first used in a dissection by Starling in December 1902, when he opened the dog’s abdominal cavity and ligated the pancreatic duct. For the next two months, the dog lived in a cage and reportedly upset people with his continual howling. He was brought back to the lecture theatre in February 1903, during which he was strapped to the operating board and muzzled, according to standard procedure of the day. The experiment reportedly included a re-opening of the abdominal cavity, inspection of the ligation and exposure of the salivary glands, with an unsuccessful demonstration of the independence of salivary pressure from blood pressure. Anesthesia was accomplished via a prior injection of morphine, then a mixture of chloroform, alcohol and ether was administered by a tube in the dog’s trachea. After the experimental session, the dog was dispatched with a knife by student Henry Dale (1875-1968), who would go on to win a Nobel Prize in 1936 for his work on acetylcholine.

The experimental demonstration in February 1903 had been infiltrated by two Swedish women antivivisection activists and medical students, Louise Lind-af-Hageby (1878-1963) and Leisa K. Schartau, from the London School of Medicine for Women, a vivisection-free college. From their report of the demonstration, included in the second edition of their 1903 book entitled Shambles of Science: Extracts from the Diary of Two Students of Physiology, arose both a libel case relating to infringements of the 1876 Cruelty to Animals Act, brought forward and eventually won by Bayliss in November of 1903, and a public memorial in the form of a bronze statue of the dog, complete with an antivivisectionist inscription, that was erected in Battersea in 1906.

Approximately one year after it was put up, a 24-hour police guard against the “anti-doggers” – who were mainly medical and veterinary students – began to place a significant burden on the Battersea Council budget and create worries about damage to property and laboratory material. The anti-brown dog protests escalated to riots in December of 1907, when the students tried to pull the memorial down, and they reportedly broke into suffragist and antivivisectionist meetings, sometimes violently. Over the following weeks, the rioters were countered by an alliance of trade unionists and women suffragists, and controversy continued to simmer over the next few years. The statue was quietly removed during the night of March 10, 1910, by Council workmen with police accompaniment. Ten days later, there was a demonstration by 3000 antivivisectionists demanding the return of the statue, but it was not until 1985 that a new Brown Dog memorial was erected in the Battersea Park with a new inscription.

The Brown Dog Affair can be viewed in hindsight as a significant turning point in the conflict between scientific progress and antivivisectionism. On one hand, the controversy united a sector of popular opinion, women suffragists and working class men, who all came together to defend the dog not only due to antivivisectionist sentiment, but also because the statue had become a symbol of victimhood, oppression by wealthier, establishment forces, and the casual but deliberate cruelty inflicted on the disenfranchised. This alliance of the worker classes, the predominantly middle-class woman suffragists and the burgeoning socialist and radical elements of society was a solidarity born of identification with – literally, in this case – the underdog. However, as Lansbury notes in her book, “the cause of animals was not helped when they were seen as surrogates for women, or workers, or when they were translated into fictions, no matter how appealing.”18,p.188 In other words, humans would continue fighting their own political battles, and scientific progress using animal subjects would not be arrested by this type of popular sentiment.

Meanwhile, events that were more international in scope would soon enfold the Western world in a conflict of an unprecedented scale. Class and gender-related activism would not be remobilized until after 1918, by which time both movements, not to mention the body of medical knowledge, had undergone a sea change. Antivivisectionism fell into a dormant state, but it was to re-emerge in the form of animal welfare concerns in the 1920s and beyond.

Click here for Part II (1914-1970).

Click here for Part III (1970-2009).

REFERENCES

1. Sechzer JA. The Ethical Dilemma of Some Classical Animal Experiments. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 406: June 20, 1983.

2. Rivers Singleton, Jr. Whither Goest Vivisection? Historical and Philosophical Perspectives. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 37(4): 576-594, 1994.

3. http://www.anesthesia-nursing.com/ether.html

4. Gordon-Taylor G. Sir Charles Bell: His Life and Times. E. and S. Livingston, Ltd. Edinburgh and London, 1958; p.109-112.

5. http://www.medarus.org/Medecins/MedecinsTextes/bernard_cl.html

6. Porter R. The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity. W.W. Norton & Company, New York, United States: 1998; p. 338.

7. Tacium Ladry D. Searching for the Magic Bullet: Veterinary Experiences with the First Antibiotic. Veterinary Heritage, Vol. 25(1): 1-6, May 2002.

8. Bernard C. An Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine. Chapter III. Dover Publications: New York, United States. p.102. (The original work was published in France in 1865. This edition was translated into English by Henry Copley Greene.)

9. Preece R. Darwinism, Christianity and the Great Vivisection Debate. Journal of the History of Ideas, 64(3):399-419, 2003.

10. Connor JTH. Cruel Knives? Vivisection and Biomedical Research in Victorian English Canada. Canadian Bulletin of Medical History, 14: 37-64, 1997.

11. Nelson H. Experiments with the Sulphuric Ether Vapour. British American Journal of Medical & Physical Science, 3:34-36, 1847-1848.

12. Martineau JC. A Historical Survey of Vivisection from Antiquity to the Present. Veterinary Heritage, 19(1): 8-10, 1998.

13. Dawson PM. A Biography of François Magendie. Albert T. Huntington: New York, United States: 1908.

14. Sewell A. Black Beauty. Jarrod & Sons, England: 1877. (The novel has not been out of print since first printing.)

15. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Beauty

16. http://www.northern.edu/hastingw/sewell.htm

17. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beautiful_Joe

18. Lansbury C. The Old Brown Dog: Women, Workers and Vivisection in Edwardian England. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press; 1985.

19. Birke L. Supporting the underdog: feminism, animal rights and citizenship in the work of Alice Morgan Wright and Edith Goode. Women’s History Review, 9(4):693-719.

20. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frances_Power_Cobbe

21. Bittel C. Science, Suffrage, and Experimentation: Mary Putnam Jacobi and the Controversy over Vivisection in late Nineteenth-century America. Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 79:664-694, 2005.

22. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brown_Dog_affair

April 14, 2012 at 3:48 pm

[…] Germany, only Saxony eventually banned shehitah in 1897. While many supporters of the campaign were anti-vivisectionists or were concerned about the treatment of animals in abattoirs, there is no coincidence that this […]

September 16, 2013 at 1:26 am

[…] feminists’ interest in vegetarianism stemmed partly from their opposition to animal cruelty and vivisection, but was also the product of the Theosophical Society’s influence over so many late-Victorian […]

March 6, 2015 at 7:17 pm

[…] about their intelligence and emotions go back at least a few hundred years. See, for example, debates about vivisection in 19th century UK, and in particular the old brown dog affair. As a result, we are starting to see […]

July 5, 2016 at 1:12 am

[…] Black Ewe (2008): A History of Antivivisection from the 1800s to the Present: Part I, Part II, Part […]

April 2, 2017 at 8:31 pm

[…] A History of Anti-vivsection from 1800s to the Present: Part I (1800-1914). […]

July 3, 2017 at 8:11 am

[…] A History of Anti-vivsection from 1800s to the Present: Part I (1800-1914). […]

January 14, 2019 at 10:54 am

[…] the now-famous book published by Peter Singer in 1975. Looking back further, you might say that the antivivisection movement starting in the mid-1800s was the beginning of the modern animal rights movement. Or you could even look back much further to […]

February 6, 2022 at 10:10 pm

[…] the now-famous book published by Peter Singer in 1975. Looking back further, you might say that the antivivisection movement starting in the mid-1800s was the beginning of the modern animal rights movement. Or you could even look back much further to […]